Repairing a 1957 truck fender demands not just technical proficiency, but also an appreciation for authenticity. As fleet managers and trucking company owners invest in preserving vintage vehicles, understanding the intricacies of fender repair is paramount. The fender of a vintage truck is vital for both functionality and aesthetics, shielding critical vehicle components while contributing to the overall character of the truck. This article navigates through assessing damage, applying repair techniques, and sourcing appropriate parts to achieve a restoration that meets both operational and historical standards. Each chapter lays down integral foundations to ensure successful fender repair, keeping your 1957 trucks operational and looking their best.

Reading the Steel: Assessing Damage and Planning Restoration for a 1957 Truck Fender

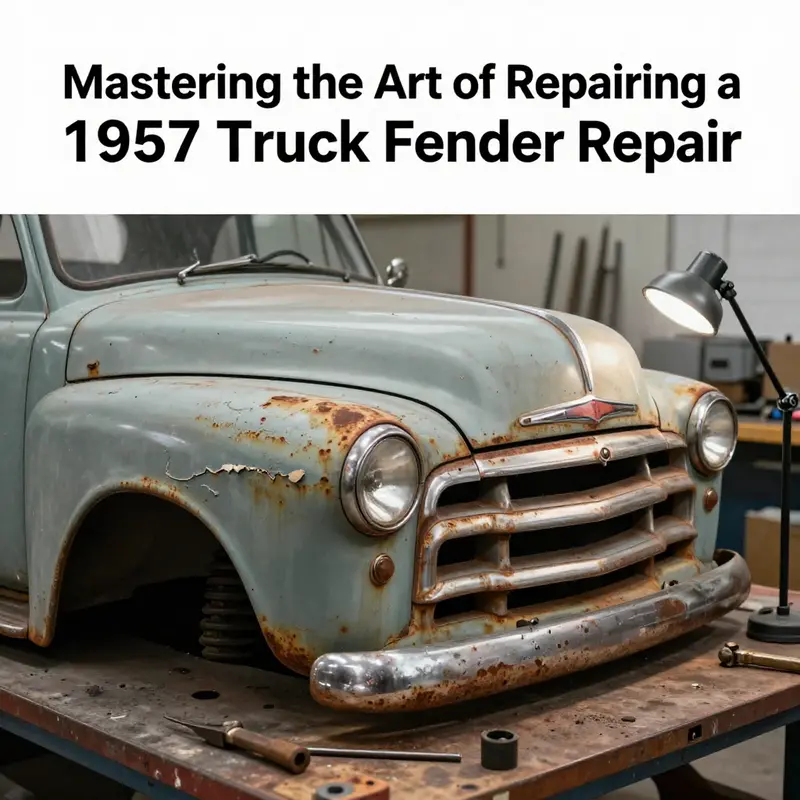

The fender on a 1957 truck is more than a shield over a wheel; it is a curved sheet of history that carries both the imprint of decades of road life and the practical duty of protecting the fragile geometry of the rear suspension and cargo area. When that fender has been repurposed for a vintage camper or a personal tribute to a bygone era, the repair becomes a careful negotiation between authenticity and practicality. The steel you are working with was formed in a different kind of factory, from alloys that behaved once, uniformly, under a different set of pressures. Time, moisture, and road grit have a way of taking their toll, introducing rust where it once sang with a clean, hard shine. In such a setting, assessing damage is not merely noting a dent or a hole; it is reading a piece of metal that has learned to tell a story about the miles it has carried and the conditions it has endured. The approach to assessment, then, must be patient, methodical, and anchored by an eye trained to preserve the vehicle’s original silhouette while establishing a workable path to repair that respects both strength and appearance.

To begin, visualize the fender not as a separate panel but as a component whose edges, curves, and mount points have a direct relationship with the surrounding structure. The aim is to determine whether the fender remains true to its original shape and whether the metal around it has maintained enough integrity to support a repair without introducing misalignment elsewhere. The inspection should move in an orderly sequence: first assess the exposed surface for obvious damage, then trace the damage inward toward the mounting points and inner edges, and finally check how the fender interacts with the wheel well and frame when the vehicle would be loaded and moved.

Visual inspection remains the simplest, yet one of the most telling, tools for a first pass. Dents that crowd the area around the wheel opening can be a precursor to deeper problems, especially if the metal around the dents has stretched, thinned, or lost its spring-back. Cracks and hairline fractures, particularly at stress concentrations near mounting lugs or along panel edges, are warning signs that the fender may have experienced fatigue. Rust is the quiet culprit; it often hides in layers, starting as pinholes that seem inconsequential and spreading outward as salt, moisture, and time encourage corrosion. Warping or distortion in the fender’s curve can signal a compromised crown line, which will complicate both alignment and painting later on. Even when a fender appears superficially intact, a close look at the edges where metal meets the mounting brackets can reveal whether there has been a shift in the panel’s own geometry. A misalignment here can ripple through to the wheel well and misfit body gaps elsewhere, producing a look that betrays the panel’s true age while undermining performance.

The next layer of assessment is more tactile and structural. If the metal feels thin or soft when you press with a gloved finger, or if you hear a dull, hollow sound when tapping with a small hammer or tool, you may be facing corrosion that has eaten through the back or the inner surface. Inspecting the back side of the fender is essential because rust may not be visible from the outer surface yet progress briskly from behind, where trapped moisture and road spray can accelerate corrosion. In some cases, the back of the fender will reveal pitting, scale, or a crust of corrosion that has progressed well beyond surface blemishes. If you uncover rust that has penetrated the skin to an extent where metal has thinned beyond welding tolerance, you are entering a crossroads: do you patch, do you replace, or do you re-create a panel that will faithfully reproduce the original shape? The decision hinges on the fender’s role in the vehicle’s overall stroke and silhouette. In a classic vehicle, the fender is part of the visual grammar—the sweep of the wheel opening, the line that leads into the door, the small outward flare near the bumper. Any repair must preserve that geometry as faithfully as possible.

A systematic approach to evaluating the problem invites a few practical questions. Can the damage be corrected with minor reshaping and the original metal preserved? If the metal is still sound, a dent here and a crease there can often be coaxed back into alignment with traditional metalworking tools. The tools of the trade here are humble and time-honored: a body hammer, a set of dollies, and a steady hand. The hammer and dolly method works best when the metal has retained its original thickness and the damage has not surpassed the point where the skin has stretched or torn. A patient sequence—strike gently, flip, test the fit against a straightedge or the wheel well opening, then recheck—can restore the crown line and bring the fender back to a shape that matches the surrounding panels. It is a craft that rewards restraint; overworking a single area can produce a ripple effect that sprints away from the intended silhouette.

When rust or significant corrosion has taken hold, the calculus changes. If a rusted segment has hollowed out a patch of metal or if the extent of corrosion has produced holes, the repair landscape shifts toward more invasive measures. In such cases, you may need to cut out the damaged portion and weld in a replacement patch that matches the thickness and grade of the original sheet. This is not a decision to be made lightly. Welded repairs today must anticipate heat-affected zones and the risk of warping in a panel that bears a crown line and a curved edge. The art here lies in fabricating or sourcing a patch that mirrors the original curvature and bending the patch to fit within the fender’s contour without producing a bulge or a seam that catches light differently. Compatibility is more than thickness; it is about grain direction, edge shape, and the way the patch will respond to the same stresseas the rest of the fender when the vehicle is in motion. If you do choose to replace a panel section, you must ensure the patch not only fits the opening but also preserves the fender’s ability to drain and vent moisture, and to maintain the correct relationship to the wheel well margin.

A critical element in this assessment, often overlooked, is the fender’s attachment to the frame and its mounting points. The mounting lugs may be bent, damaged, or cracked, and those points can become the anchor for misalignment if not addressed. The alignment issue is not purely cosmetic; it affects the fender’s gaps at the door seam and at the bumper line, which in turn affects how the chrome and paint will appear when finished. A precise alignment check begins with loosening the fender from its fasteners and lifting it away carefully, ensuring that the mounting holes line up with the bracketry on the frame. A quick test after removal—placing the fender back into its approximate position and checking the spread of the bolt holes—will reveal whether the fender is still true to its original shape or whether the panel has become a little off-kilter due to years of stress. If alignment is off, a combination of coaxing the panel into shape with measure and gentle hammer work, followed by the precise re-tacking of mounts, can bring the fender back to the correct geometry without sacrificing its period-accurate curvature.

The decision to repair or replace is rarely a moment of triumph; it is a careful cost-benefit analysis anchored in the vehicle’s historical integrity. If the damage is concentrated in one curved region where re-shaping and patching would require multiple seams and compromises to the panel’s curvature, resistance to patchwork may be wise. In such scenarios, a period-correct replacement fender—or a hand-formed patch from a skilled metalworker who specializes in classic American panels—may deliver a result closer to the original appearance and performance. Replacement decisions are never purely cosmetic. They hinge on whether the restored fender will align with the wheel well’s clearance, whether it can be securely attached without inducing flex, and whether the final finish will respect the original factory color and sheen. The goal is not merely a fender that looks right, but a fender that behaves right in the way road spray is repelled, water is shed, and the vehicle retains its classic silhouette under street lights or a quiet roadside dusk.

Surface preparation after any repair deserves careful attention. Whether you have shaped a dent, patched a hole, or replaced a patch, the next stage is to bring the metal to a primer-ready state. This process begins with thorough cleaning to remove oils, rust scale, and any oxidation that could impede adhesion. The surface is then sanded with progressively finer grits to create a uniform, matte finish that will welcome primer without creating a pockmarked or uneven base. Primers for vintage metal must be selected with an eye toward compatibility with the base and topcoat that will follow. The trick is to choose a primer that will seal the repaired area’s edge and avoid lifting the paint later in the fender’s life when heat and moisture cycle through the metal. When attempting to preserve authenticity, the aim is to replicate the original factory finish—both color and gloss—so that the repair fades into the vehicle’s overall narrative rather than standing out as a detour in the paintwork.

Paint and finish are, in many restorations, the last but not least stage. The color match must be carried out with care. If you can locate a period-correct shade that matches the factory color, the job becomes more faithful to the truck’s era and its overall design language. If exact matching proves elusive, you can still achieve a visually cohesive result by blending the repaired area into the surrounding panel using subtle variations in shade, noting that the finish will change subtly as the vehicle ages further under sun and weather. The finish should not merely resemble the original; it should be compatible with the fender’s texture and gloss so that reflections and highlights across the fender read as one continuous sheet rather than two separate panels.

Throughout this process, the historical authenticity of a 1957 fender must guide every decision. Modern epoxy resins and fiberglass patches appear in many repair guides, but in the context of a 1957 fender, these materials can betray the period character and the panel’s structural language. Where patches may be used, they should be approached only with the consent of a seasoned vintage-vehicle restoration expert who understands the risks and benefits unique to that fender’s metallurgy. The prudent path for most restorations is to preserve the original steel or aluminum skin whenever possible, replicating the crown line and wheel opening using traditional metalworking techniques, and relying on patchwork only when it sustains the panel’s integrity, keeps the original contours intact, and allows the final paint to lay evenly.

Because the assessment of a 1957 truck fender is rarely a solo effort, engaging with a community of experienced restorers can be a decisive advantage. A robust online resource, such as a restoration forum dedicated to classic American trucks, offers practical wisdom and peer guidance that complements personal hands-on work. It is common to encounter fellow enthusiasts who have faced similar curved challenges and can offer images, measurements, and tips that help you judge whether your fender’s geometry is recoverable. When you consult these sources, treat the shared knowledge as a compass rather than a blueprint. The fundamentals—distortion, corrosion, alignment, and material compatibility—remain constant, but the exact curvature and mounting geometry can vary with different truck models and years. A careful, collaborative approach increases the likelihood that your assessment translates into a repair path that respects the fender’s original look while delivering dependable performance on the road.

In practical terms, the assessment is a bridge between observation and action. It translates the fender’s condition into a repair plan that weighs the feasibility of reshaping, patching, or replacing against the realities of the vehicle’s use, whether it travels on quiet country roads or serves as a vintage camper that will face more weathered environments. The aim is not to produce a flawless showroom piece but to deliver a careful restoration that preserves the truck’s history, maintains structural integrity, and ensures safe operation. The process demands patience, precise judgment, and a respect for the workmanship that went into the fender in the first place. When done well, the repaired fender becomes more than a panel; it becomes a vessel that carries forward the legacy of a 1957 truck, offering shelter from the elements while inviting the next generation of restorers to learn from its curves, its scars, and its stubborn resilience.

As you move from assessment into the subsequent steps of actual repair, you will find that the insights gathered during this phase shape every decision about tooling, technique, and timing. The work you choose to undertake—whether it is careful hammering, a measured patch, or a thoughtful replacement—will align with the fender’s role in the truck’s overall design and its status as a piece of living history. The best outcomes come from a disciplined, principled approach that treats the fender with respect and acknowledges that a 1957 metal panel has a personality earned through decades of service. For those who want to deepen their exploration beyond the hands-on craft, a community of restorers and an ecosystem of resources exist to support the journey, helping to translate the assessment into a repair that endures.

To keep this discussion rooted in practical steps while honoring the broader context, consider integrating a view toward emergency planning as you undertake the work. A small, deliberate reserve for unexpected costs or additional parts can help you navigate the repair with less stress, ensuring that you neither rush a critical decision nor compromise the fender’s long-term stability. For those who seek ongoing guidance on repair readiness and budgets, a concise resource on building an emergency repair fund for truck owners can be a useful companion to the hands-on work described here.

For deeper reading and a broader spectrum of techniques, this chapter draws upon established references in classic vehicle restoration. You may also find value in exploring more formalized guidance on metal finishing, surface preparation, and color matching that has stood the test of time in the restoration community. As you gather data and measurements from your own fender, keep a notebook that captures the curvature, the dimensions of the wheel opening, the state of the mounting points, and any color-matching notes. Such a record becomes a useful reference not only for this project but for future maintenance and potential further restorations.

If you need a starting point for broader restoration context, a well-regarded external resource provides a comprehensive framework for classic car restoration, including techniques that translate well to fender work from this era. This material can supplement the practical steps above, offering structured guidance that resonates with the process of assessing, planning, and executing a repair that respects the fender’s historical identity. While the specifics of each vehicle will differ, the overarching principles—respect for original geometry, careful material choice, and thoughtful surface finishing—remain constant across projects.

As you move through the assessment and onto the repair itself, the fender’s history will continue to inform your decisions. Each cut, each weld bead, and each pass of primer will be weighed not only for how well it fixes a current problem but for how faithfully it preserves the truck’s 1957 persona. The goal is to produce a repaired fender that can endure decades more of road life and, perhaps, a few more stories around a campfire where the truck waits under a quiet sky, its curves catching the light in a way that only a well-tended, history-rich piece of metal can do. In the end, reading the steel becomes a practice of listening to the material, honoring its past, and guiding it toward a future where function and form continue to speak in the same language.

Internal link for further practical planning: for a actionable, budget-minded view that complements this technical assessment, you can explore this topic further here: emergency repair fund for truck owners.

External resource for broader restoration guidance: for in-depth techniques and historically informed methods, refer to Classic Car Restoration Handbook. This resource offers detailed, period-appropriate instructions that align with the principles outlined in this chapter. https://www.motorbooks.com/classic-car-restoration-handbook.html

Shaping History with Care: A Thorough, Authentic Approach to Repairing the Fender on a 1957 Truck

The fender on a 1957 truck is more than a panel; it is a small sculpture of the era, a piece that carries the lines of a vintage chassis and the memory of long highway miles. Repairing such a part requires a balance between reverence for the original design and practical fixes that restore function, safety, and the truck’s historic presence. When approached with patience and a clear plan, fender repair becomes a dialogue with the vehicle’s past, one that respects its stamped steel contours, preserves the line of the wheel well, and avoids over-restoration that might erase the vehicle’s authentic patina. The journey begins with a careful assessment, moves through hands-on metalwork, and ends with finishes that protect and blend into the vehicle’s overall aesthetic. Throughout, the goal is not to replace the story the fender tells but to repair its story so it can be read again by future eyes.

To start, a thorough inspection sets the tone for the entire repair. Remove the fender only when you are ready to work, and do so in a controlled environment where tools, clamps, and a work surface can be positioned without forcing the fender into awkward angles. The 1950s fender is typically a stamped steel panel with complex curves, mounting points, and a shape that aligns with the wheel well and the door line. Cracks, rust, and warping must be diagnosed in layers. Tiny hairline cracks near mounting flanges can propagate if left unattended, while rust that has penetrated through the metal threatens the panel’s integrity. Warping often presents as a distorted crown or a misalignment with the wheel opening. At this stage, you’re listening to the fender’s story—the sounds of metal breathing as you gently tap with a hammer, the way rust flakes off when you probe with a pick, the way metal behaves when you try to bring it back to shape. This is not a quick fix; it is a careful reconstruction.

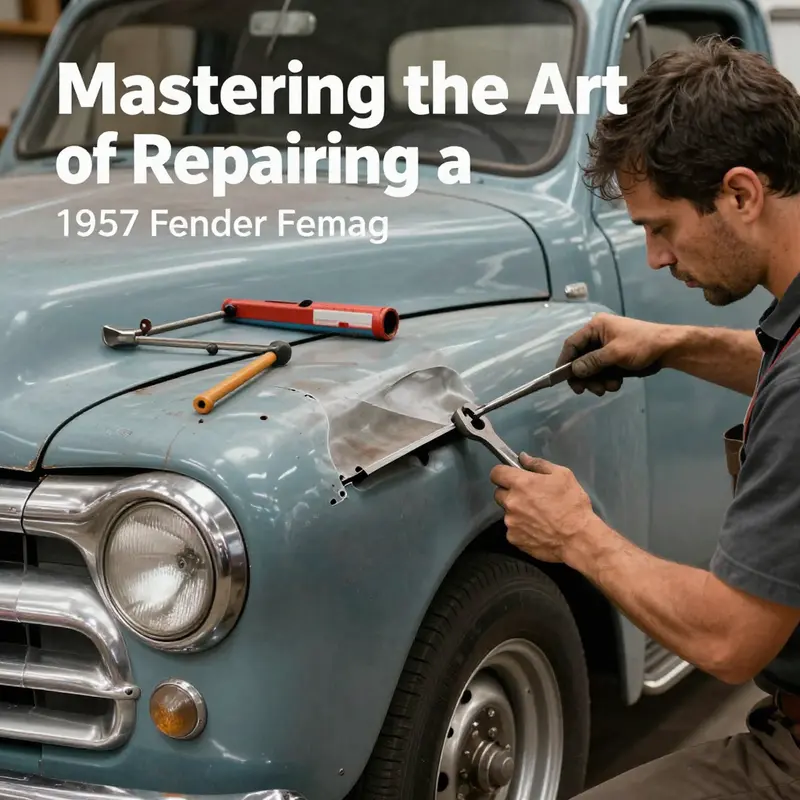

When the fender has been detached, the work moves inward to the metal itself. For minor dents with intact paint, a cautious approach can restore the original contour without compromising the surface. Paintless dent repair (PDR) can be an appropriate first step if the damage is shallow and the paint around the dent is sound. PDR works best when the dent is relatively small and the panel’s back side is accessible. It’s a precision process, a dance between pressure and leverage that relies on specialized tools and a trained eye. On a vintage fender, the risk of stretching or creating new distortions is real, so the decision to use PDR should be made with experience and careful assessment of the dent’s depth and the condition of the surrounding metal. If the dent is shallow and the paint surface remains intact, PDR can salvage contour without the need for filler or repaint. If the dent is deeper or the paint shows cracks, traditional metalworking becomes the more appropriate path.

Significant damage or paint compromise calls for traditional bodywork techniques. The body hammer and dolly are the craftsmen’s tools for re-establishing the fender’s original curvature. The process starts with a light, even approach: the hammer strikes lay the foundation of a new crown, while the dolly behind the metal provides a stable surface to prevent backward stretching. This is a controlled dialogue with the metal, and you must be ready to switch between gentle persuasion and firmer adjustments as the fender’s shape returns to its intended silhouette. Patience matters because the first few passes can reveal more subtle high spots or low spots that were not visible at the outset. The objective is a smooth, uniform curvature that follows the fender’s factory geometry, particularly around the wheel opening where stiffness and contour are essential for adequate clearance.

Once the major contours are addressed, you shift to smoothing the surface and reestablishing a uniform base for finishing. Sanding is a critical stage designed to reveal whether the panel has retained its integrity after the hammering. Begin with a coarser grit to remove pockmarks or minor distortions, then progressively move to finer grits to achieve a uniform surface. This step also serves as an assessment: if you see fine cracks opening up, especially at edges or around mounting points, it’s a sign that the fender’s structure has endured more stress than anticipated. In such cases, straightening and reinforcement may be necessary, potentially involving stitch-welding along seam areas or adding small patch pieces to restore rigidity. When patches are required, they should be cut to mirror the original edge and curved to preserve the fender’s line. The patch should be welded with care to minimize heat distortion, and any heat-affected zones must be treated to prevent future rust or loosening of the patch.

Rust treatment is the next essential phase. Rust in an old fender is more than a surface nuisance; it is a sign of where metal has thinned and where future failure can occur if left unaddressed. Begin by removing all loose rust and scale with mechanical means while keeping heat away from the surrounding paint. A rust inhibitor or converter can help stabilize the remaining iron and prepare the surface for primer. After treatment, any compromised areas must be evaluated for the feasibility of salvage versus replacement. For deeply pitted sections where the metal has lost substantial thickness, replacement panels or robust patchwork may be the more reliable choice to preserve safety and structural integrity. When patching is chosen, the repair should be designed to minimize the amount of bare metal exposed to the elements after repainting. This means ensuring that the patch edges are flush and that seams do not become potential corrosion sites.

The next phase centers on primer and sealant decisions. Priming serves two purposes: it seals the metal to prevent further corrosion and provides a steady, uniform surface for paint adhesion. Opt for a high-quality automotive primer designed to bond with steel and to resist rust. Application should be even and conservative, avoiding thick builds that can trap moisture or fail under temperature changes. In a vintage truck restoration, color matching becomes a crucial part of the process. The objective is to recreate the original look without attracting undue attention to the repair. Factory color codes, when available, provide a guide to the correct shade. In practice, color matching can be a challenge because original paint formulations differ from modern finishes. Modern color matching services can analyze the original paint code and help reproduce a finish that blends with the rest of the vehicle. The painter’s technique matters as much as the color, so an even, consistent spray pattern, proper humidity, and controlled curing conditions contribute to a believable, authentic result.

Painting the repaired fender requires careful attention to the finish and to the panel’s relationship with the others. This is where the period look comes into play: older finishes often used enamel or lacquer that aged with a certain luster. The goal is to achieve a finish that matches the rest of the body not only in color but in gloss and texture. The process often involves multiple coats and a careful cure. If possible, the fender should be allowed to cure in a clean, temperature-stable environment to minimize dust and moisture infiltration. Finally, polishing the surface after curing helps to bring the finish to a smooth, film-like quality that sits respectfully with the adjacent panels. The entire painting step is where the restoration philosophy shows itself most clearly: the fender should appear as part of a coherent whole, not as a separate patch.

Proper reattachment to the truck involves more than simply rebolting the fender in place. You need to ensure alignment with the frame, wheel well, and adjacent panels. Mounting hardware should be checked for wear and corrosion, and fasteners must be torqued to appropriate specifications to avoid unnecessary stress on the newly repaired panel. A misaligned fender can cause rubbing, which not only damages the paint but can lead to accelerated wear on the tire and suspension components. The alignment process should be deliberate and incremental: loosely fit the fender, check the alignment visually and with any available reference lines on the truck, then tighten gradually as you verify consistent gaps and clearances. The wheel opening must have adequate clearance to allow for suspension travel and tire movement without contact. It is helpful to run a quick routine test by rolling the vehicle slowly and observing any contact points. This step reinforces a practical truth about vintage repair work: geometry and fit matter as much as the surface finish.

In the broader context of restoring a 1957 truck fender, sourcing period-correct parts can be a meaningful part of the project. Some projects benefit from replacing only the damaged portions of a fender with new or refurbished panels that match the original geometry. For those who aim for high authenticity, period-correct replacement fenders from specialty suppliers who understand the geometry and styling of 1950s trucks are worth pursuing. The decision to patch or replace depends on the fender’s overall condition and the intended final appearance. A well-executed patch can preserve more original metal, while a replacement panel can guarantee a pristine contour and a longer lifespan. Each option has its own set of challenges, including differences in fit, mounting points, and the finish required to make the repair visually disappear from casual observation.

The restoration path is rarely a straight line. Even when the goal is faithful reproduction, the process is iterative: you assess, you repair, you refine, and you recheck. The fender’s final appearance should harmonize with the vehicle’s lines and the driver’s sense of authenticity. For the dedicated hobbyist, this means accepting small trade-offs between absolute original material and practical stability. It might involve a careful blend of old metal, patched where necessary, finished in a paint that replicates the aesthetic of the era while also offering modern protection. A successful repair is one that you can point to with confidence as having restored both function and shape, so the fender is capable of shielding the wheel well while not distracting from the truck’s classic silhouette.

As you move toward the finish line, consider the broader resources available to a restoration project. Detailed guidance from seasoned restorers, especially online communities that focus on classic American trucks, can be invaluable in making decisions about technique, materials, and authenticity. These communities emphasize the balance between preserving historical accuracy and applying modern, durable repair methods. For readers who want a practical sense of how other restorers approach 1957 fender work, the Classic Truck Restoration Forum offers a wealth of peer-reviewed discussions and expertise that can illuminate tricky corners or confirm a chosen method. And to keep your project feeling connected to a larger tradition of repair and maintenance, a dedicated resource like the Master Truck Repair LLC blog can provide accessible explanations and broader context on related topics, from chassis health to bodywork strategies. You can explore further reflections and real-world examples there, which helps maintain a continuous learning loop rather than treating the fender repair as a one-off task. See more at the Master Truck Repair LLC blog for related discussions and guidance. For active engagement with practitioners who emphasize historical accuracy and practical techniques, consider visiting the online forum and sharing your own progress, questions, and results. A collaborative approach often yields insights that solitary work cannot. The fender repair on a 1957 truck is, in many ways, a quiet apprenticeship—one that connects the builder with the era’s craftsmanship while building a reliable, road-ready vehicle for years to come.

In closing, repairing a fender from a 1957 truck is a careful blend of craft, patience, and respect for the vehicle’s original design. It begins with a clean slate that respects both metal and finish, continues with a measured approach to dent repair or patching, and ends with a finish that protects and honors the car’s historical presence. The process invites you to listen to the metal and observe the lines, to make methodical decisions rather than rushed ones, and to document the decisions so future restorers understand the choices that shaped the final look. The result is more than just a repaired panel; it is a restored piece of history, a fender that speaks of the road it once traveled and the hands that preserved it for the next chapter in its lifelong journey. For those pursuing a deeply authentic restoration, every step—from the first crack of rust inspection to the last polished edge—contributes to a believable, enduring tribute to the 1957 truck’s enduring character. If you want to continue exploring related techniques and historical nuances, you can consult the community-driven resources that frame this work within a larger tradition of classic truck restoration. And remember, the path to an authentic repair lies not only in the tools you use but in the care with which you approach the fender’s history. For ongoing reading and practical advice, visit the Master Truck Repair LLC blog. External resources and discussions provide ongoing context and can be a reassuring companion as you progress through these steps, including the detailed technical discussions found on the Classic Truck Restoration Forum: https://www.classictruckassociation.org/forums/restoration-tips/1957-truck-fender-repair

null

null

Final thoughts

Repairing a fender on a 1957 truck requires meticulous attention to detail and knowledgeable assessment of damages. Each step from assessing damage, applying the right repair techniques, to sourcing period-correct parts plays a crucial role in ensuring that the vehicle not only operates effectively but retains its historical value. Fleet managers and trucking company owners who understand these nuances can safeguard their investments by preserving the authenticity and functionality of their vintage trucks, ensuring these vehicles remain a treasured part of their operations for years to come.